Development of two-phase hyperbolic models that incorporate granular-dilatancy and pore-pressure feedbacks, informed by experiments at the USGS debris-flow flume. The model basis of the D-Claw software.

This page features material and excerpts from the companion papers:

-

A depth-averaged debris-flow model that includes the effects of evolving dilatancy: 1. Physical basis. R.M. Iverson and D.L. George, 2014. Proc. R. Soc. A, 470 (2170). pdf

-

A depth-averaged debris-flow model that includes the effects of evolving dilatancy: 2. Numerical predictions and experimental tests. D. L. George and R.M. Iverson, 2014. Proc. R. Soc. A, 470 (2170). pdf

Abstract

To simulate debris-flow behaviour from initiation to deposition, we derive a depth-averaged, two-phase model that combines concepts of critical-state soil mechanics, grain-flow mechanics and fluid mechanics. The model’s balance equations describe coupled evolution of the solid volume fraction, m, basal pore-fluid pressure, flow thickness and two components of flow velocity. Basal friction is evaluated using a generalized Coulomb rule, and fluid motion is evaluated in a frame of reference that translates with the velocity of the granular phase. Source terms in each of the depth-averaged balance equations account for the influence of the granular dilation rate, defined as the depth integral of solid-phase divergence. Calculation of the dilation rate involves the effects of an elastic compressibility and an inelastic dilatancy angle proportional to m − meq, where meq is the value of m in equilibrium with the ambient stress state and flow rate. Normalization of the model equations shows that predicted debris-flow behaviour depends principally on the initial value of m − meq and on the ratio of two fundamental timescales. One of these timescales governs downslope debris-flow motion, and the other governs pore-pressure relaxation that modifies Coulomb friction and regulates evolution of m.

Introduction

Depth-averaged models are commonly used for shallow-flow hydrodynamic modeling and have been extended to multi-component granular flows such as landslides. However, standard single-phase models that employ adapted rheological rules for a single-phase fluid are innadequate for the complex dynamics of landslides and debris flows. Spatial and temporal changes in macroscopic material behaviour that result from local rearrangements of grains and attendant evolution of pore-fluid pressure pose fundamental challenges for continuum mechanical modelling of debris flows. The most conspicuous transitions occur as debris mobilizes from static material on slopes, liquefies and flows rapidly, and later regains rigidity during consolidation of deposits. Most debris-flow models neglect these transitions, and instead treat rheology or depth-averaged flow resistance as inherent properties of debris. With this approach, flow dynamics simulations typically employ basal flow resistance coefficients less than half as large as those necessary to statically balance forces at flow initiation sites. Unbalanced initial states are held in check by assuming that an imaginary dam restrains the debris until the modeller issues a command, but use of this type of initial condition compromises physical relevance.

By contrast, most natural debris flows commence when balanced forces are infinitesimally perturbed. Flow onset commonly results from rainfall or snowmelt that triggers failure of debrismantled slopes or mobilization of scree in steep rills and gullies. As masses of water-saturated grains begin to move, however, the governing force imbalance can evolve dramatically owing to pore-pressure feedbacks that modify the apparent rheology of the debris. Differences between this type of behaviour and behaviour that arises from a stipulated rheology and force imbalance have great practical as well as theoretical significance, because pore-pressure feedbacks can determine whether a rapid debris flow develops at all—as opposed to a creeping landslide that moves imperceptibly or intermittently downslope.

Objectives

Our chief goal is seamless simulation of debris-flow motion from initiation to deposition without any redefinition of governing equations, re-evaluation of parameters or restructuring of numerical methods. We pursue these goals by formulating a depth-averaged model that allows feedbacks to develop during coupled evolution of solid and fluid volume fractions, porefluid pressure and debris-flow velocity and thickness. The feedbacks involve dilatancy – the state-dependent propensity of granular materials to undergo changes in solid volume fraction as they shear. Well-known since the time of Reynolds, variable dilatancy underpins the critical-state theory of soil mechanics, and it plays a key role in determining of the continuum-scale rheology of dense granular flows. Previous depth-averaged debris-flow models have included effects of solid–fluid interactions, and a few have accounted for evolution of solid and fluid volume fractions. However, no previous model has explicitly considered dilatancy coupled to pore-pressure feedbacks that mediate transitions between static and dynamic states.

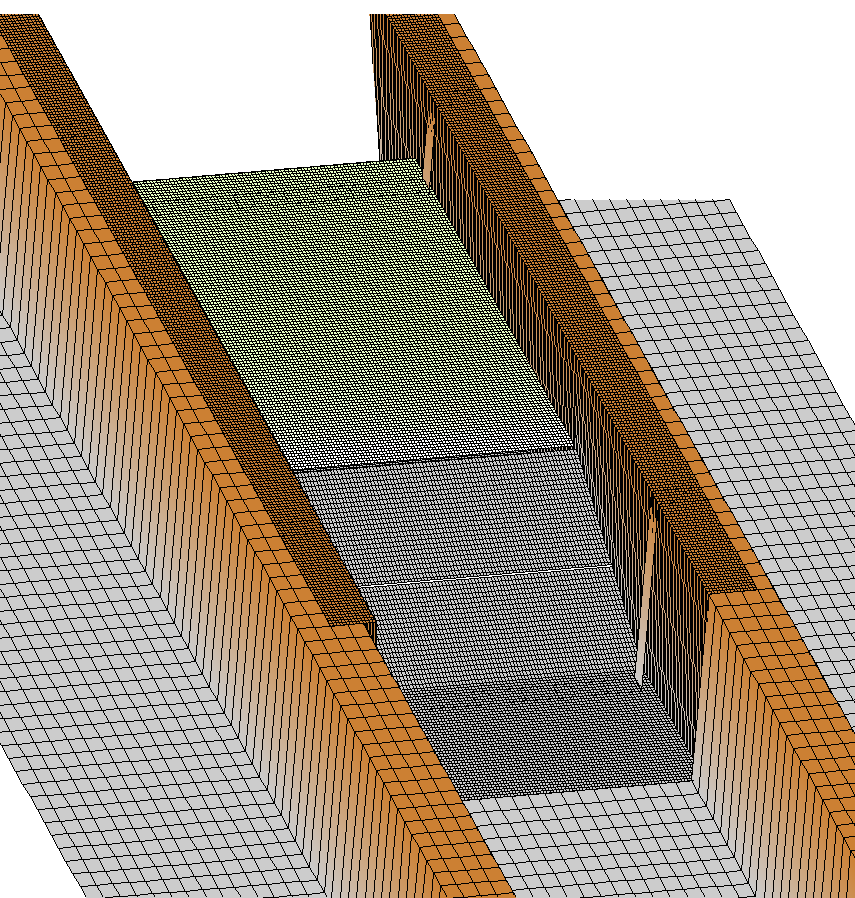

Our model is a depth-averaged granular-fluid model in the form of a two-phase, strictly hyperbolic system for depth, momentum, volume fractions, and pore-fluid pressure. Like all depth-averaged models, our model neglects some details of three-dimensional behaviour. It nevertheless provides predictions that can be rigorously tested because it computes flow depths, velocities and basal pore pressures with a resolution similar to that of the most-detailed debris-flow data collected to date. Use of the solid volume fraction as an additional prognostic variable expands the possibilities for future model applications.

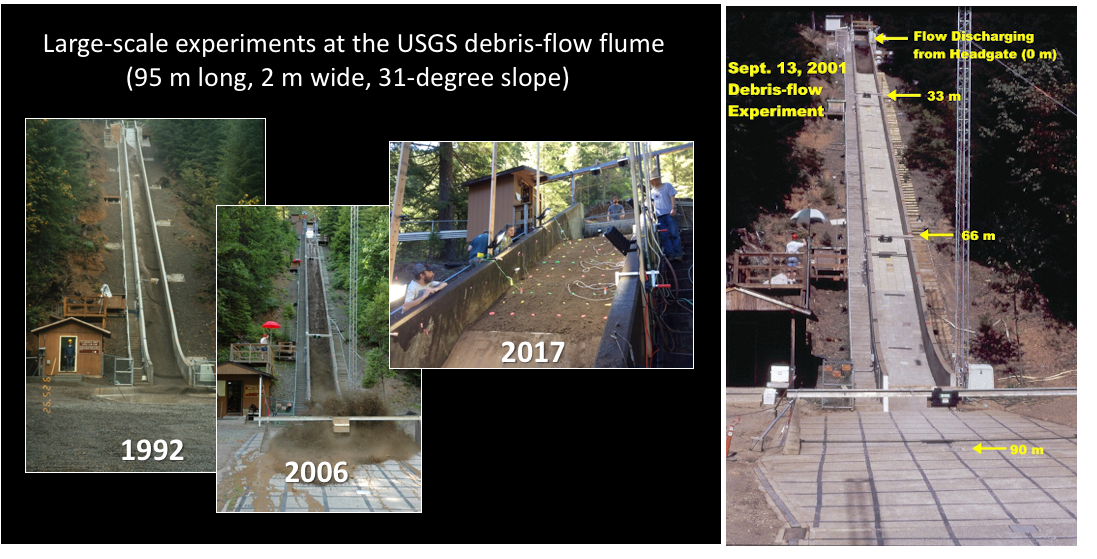

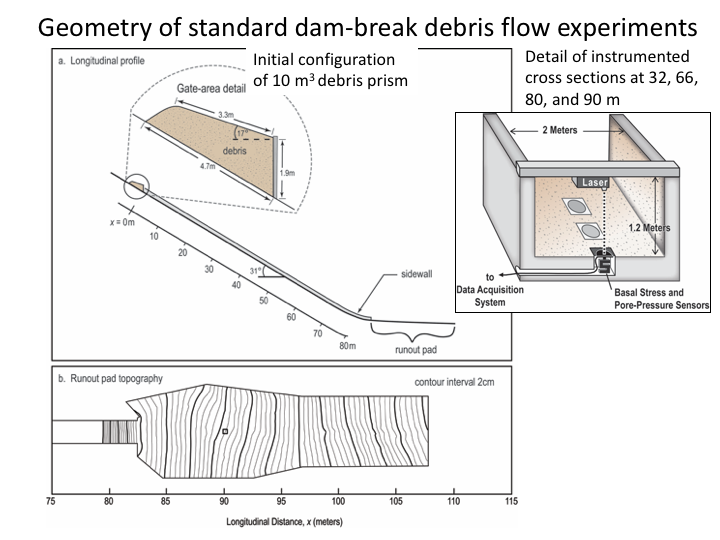

Model development and validation utilizing the USGS debris-flow flume

To test D-Claw, we present simulations of two types of large-scale experiments conducted at the USGS debris-flow flume (Figure 1). In the first type of test, we address short-timescale dynamics during onset of debris-flow motion triggered by gradually rising pore-fluid pressures in static slopes. In the second type, we address dynamics over the longer timescales that are relevant during subsequent downslope motion, runout and deposition. Traditionally, these two distinct problems have been treated with dissimilar models, one for onset of slope instability and one for the dynamics of ensuing motion. By contrast, D-Claw simulates both flow onset from an initially balanced equilibrium state and flow dynamics in states that are far from equilibrium.

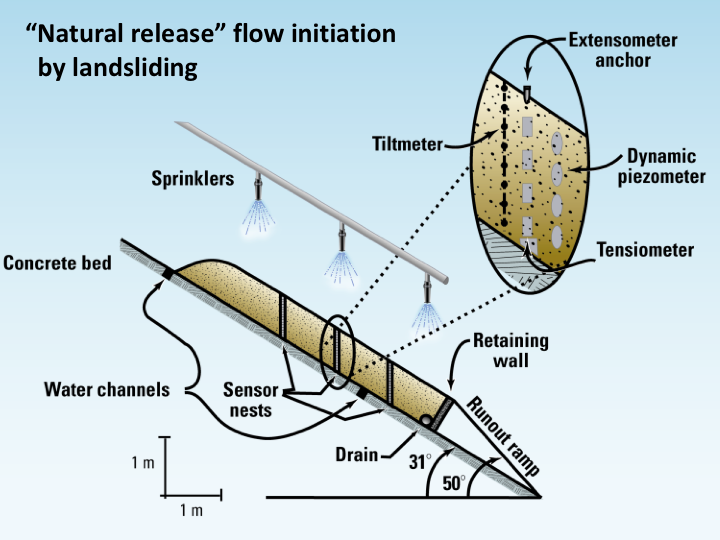

Predictions of slope stability and flow mobilization: natural release experiments.

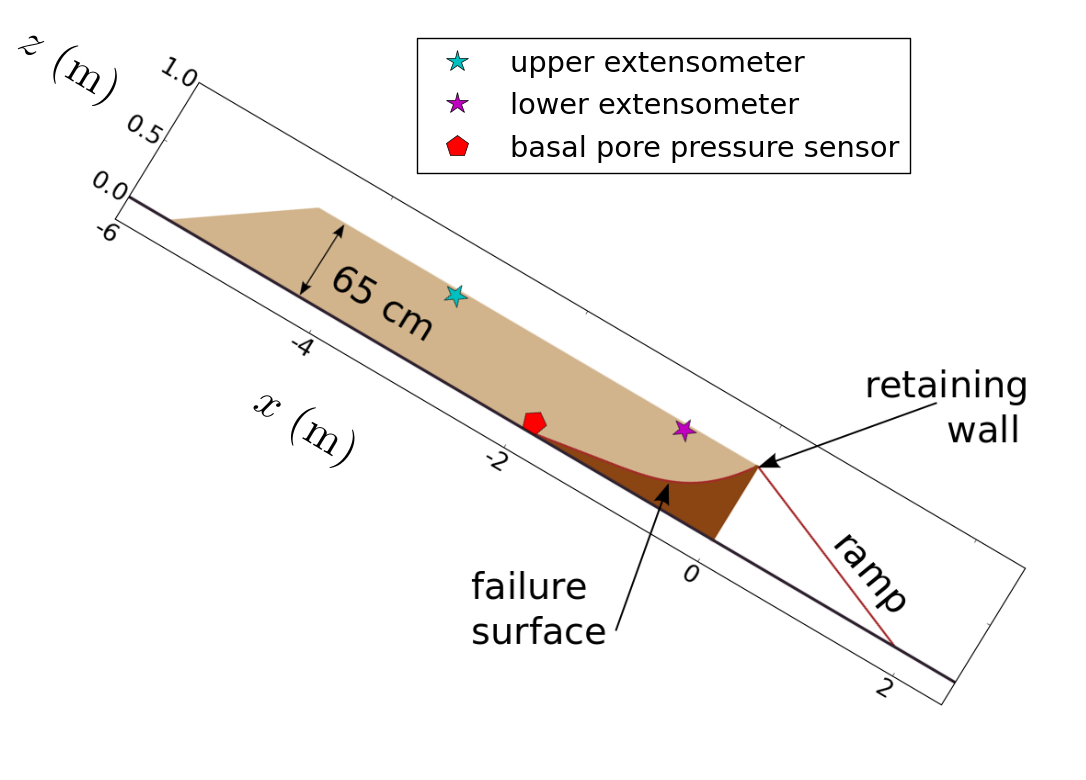

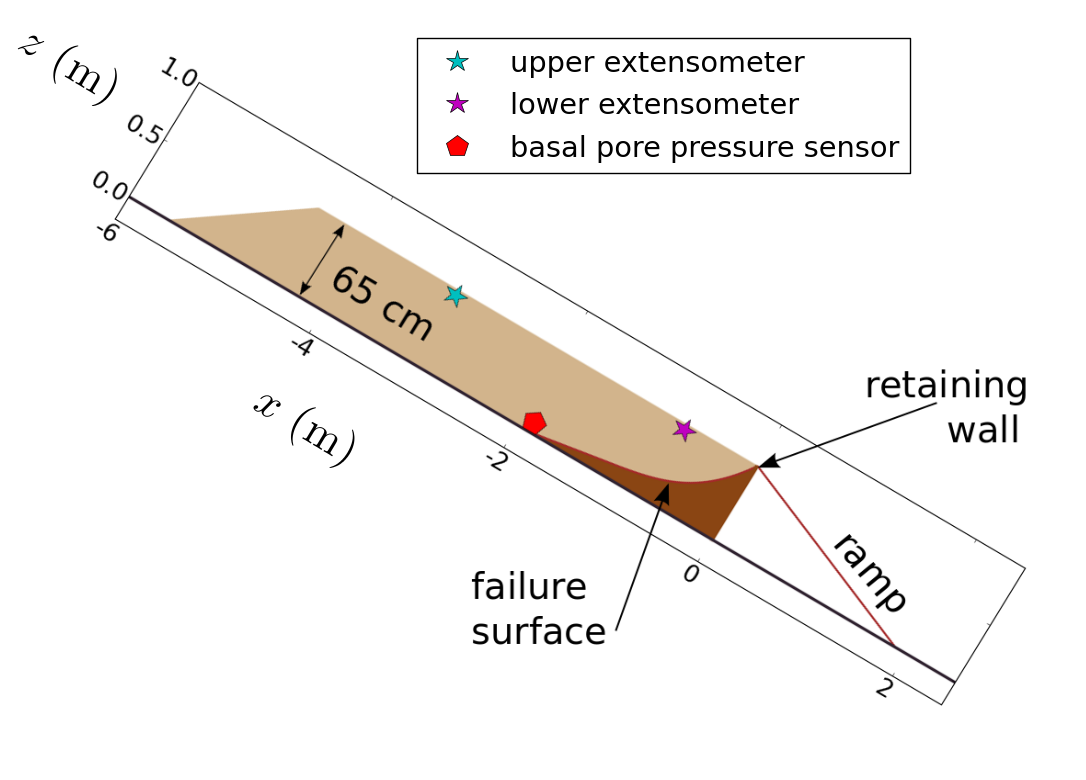

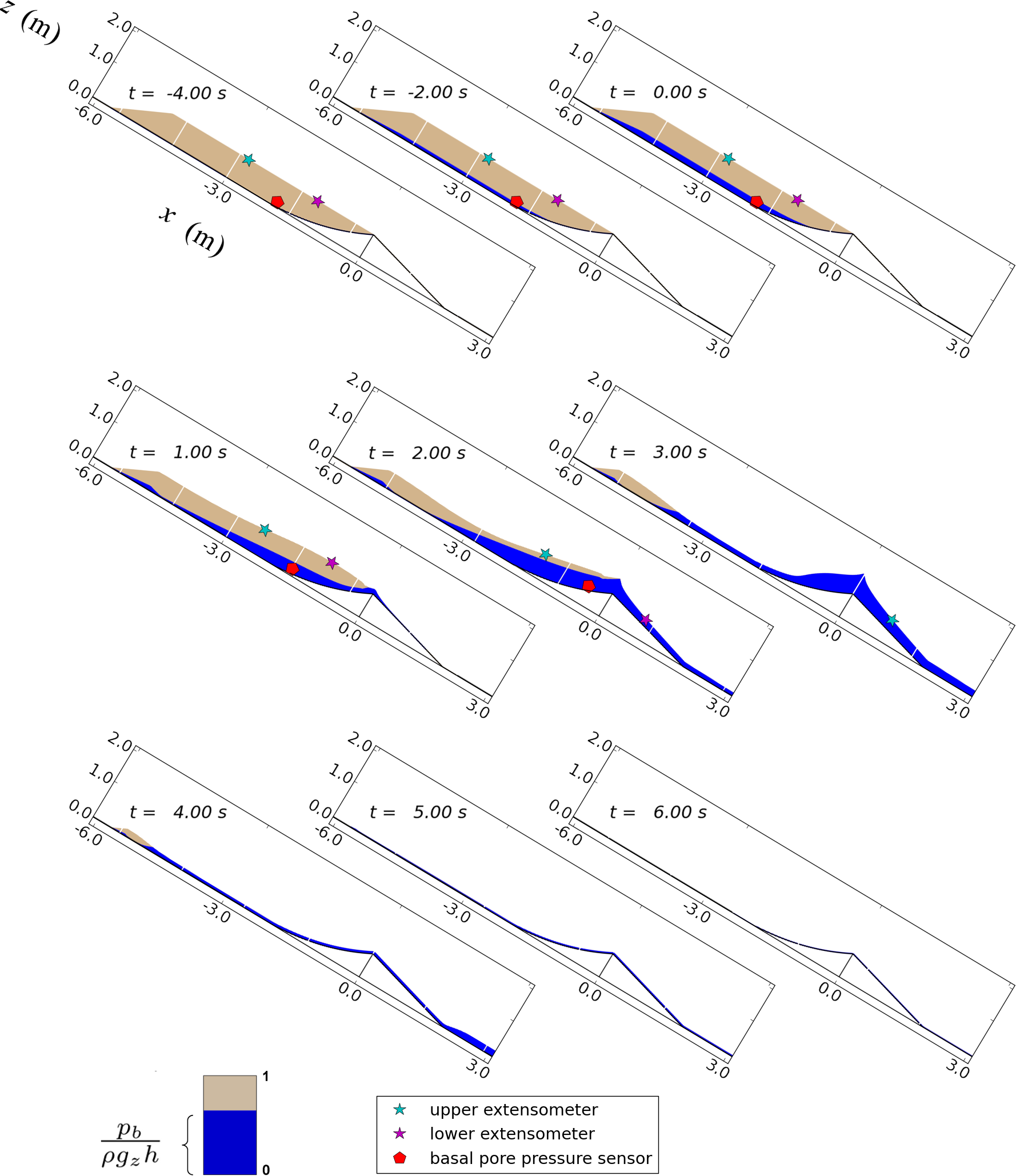

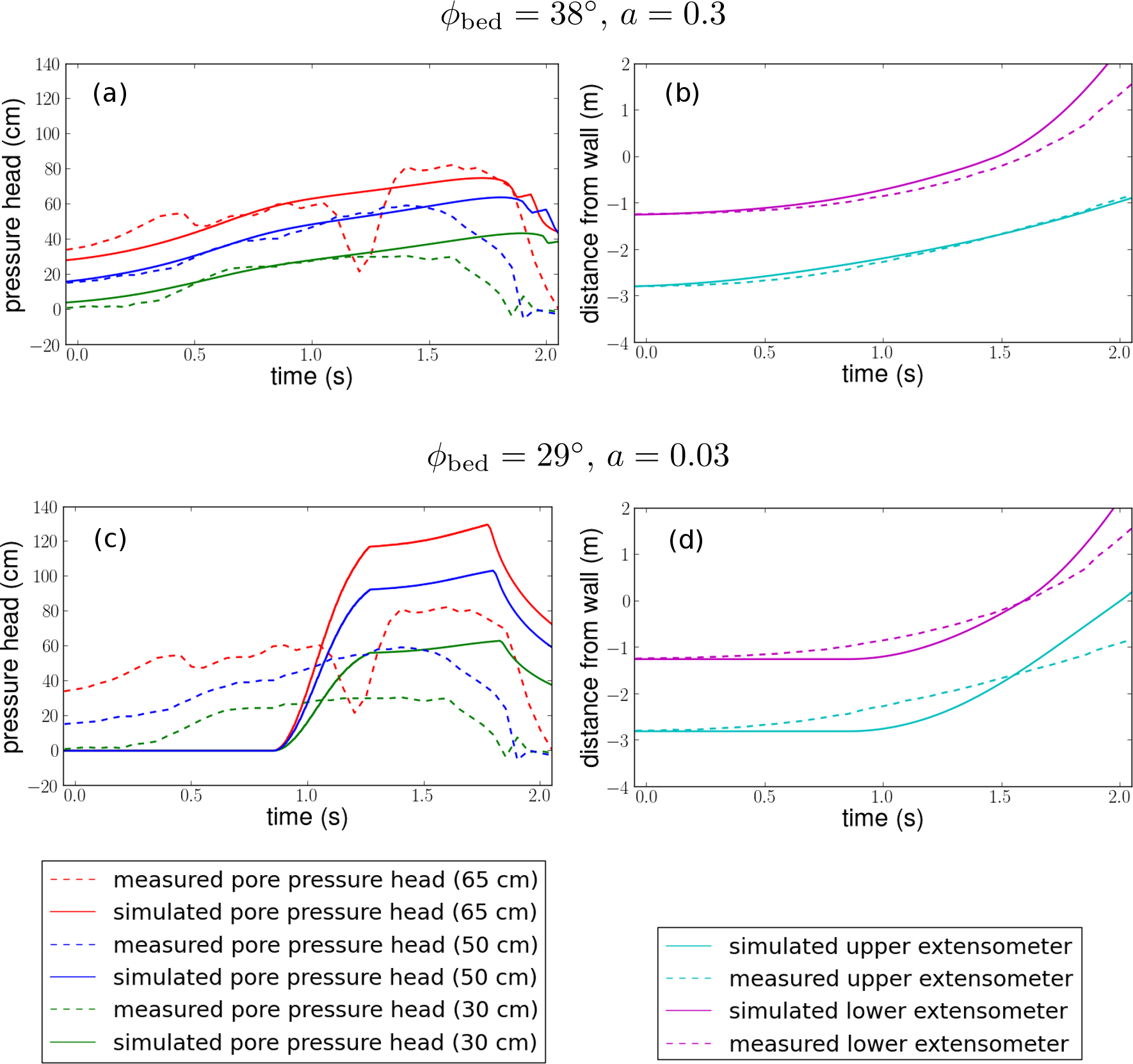

In this section, we investigate D-Claw’s ability to predict debris-flow mobilization from an initially stable sediment mass. In each of the mobilization experiments (described by Iverson et al. 2000), a 6 cubic meter rectangular prism of sediment was placed behind a retaining wall positioned normal to the bed. Rising pore-water pressures that triggered slope failure were generated by controlled watering. Evolving pore-water pressures and slope deformation were monitored continuously by a network of piezometers, tensiometers, subsurface tiltmeters and surface extensometers.

We consider repeated experiments in which only the initial sediment porosity is intentionally varied. In some experiments, the sediment was loosely placed resulting in initial solid volume fractions m < 0.5. In other cases, the sediment was densified through vibrational compaction of multiple layers resulting in initial solid volume fractions m > 0.6. Ancillary testing revealed that the critical-state solid volume fraction for this sediment at appropriately low confining stresses was about 0.56. We classify the initial states m< 0.56 as ‘loose’, while those in experiments with m>0.56 were classified as ‘dense’.

During slope failure, loosely packed sediment quickly liquefied and transformed into rapid debris flows. This behaviour resulted from sediment contraction upon shearing, evidenced by a dramatic, contemporaneous increase in porefluid pressure. With densely packed sediment, on the other hand, slope failures exhibited self-stabilizing behaviour, because pore-fluid pressures decreased as the deforming sediment dilated. In such cases, landslides crept slowly and sometimes intermittently downslope. These contrasting styles of behaviour test not only D-Claw’s ability to seamlessly simulate the transition of a stable mass into a moving mass, but also the model’s ability to regulate evolution of pore-fluid pressure and thereby influence the degree and nature of landslide mobilization.

Case 1: loose-sediment experiment: dilatancy feedbacks lead to liquefaction and runaway acceleration.

We first consider model performance in simulating an experiment with loosely packed sediment. In these experiments and simulations, initial failure of the sediment results in profound weaking associated with liquefaction and runaway acceleration. (George & Iverson, 2014, provides a more detailed description of model results and piezometer and extensometer data.)

Case 2: dense-sediment experiment: dilatancy feedbacks lead to slow episodic motion.

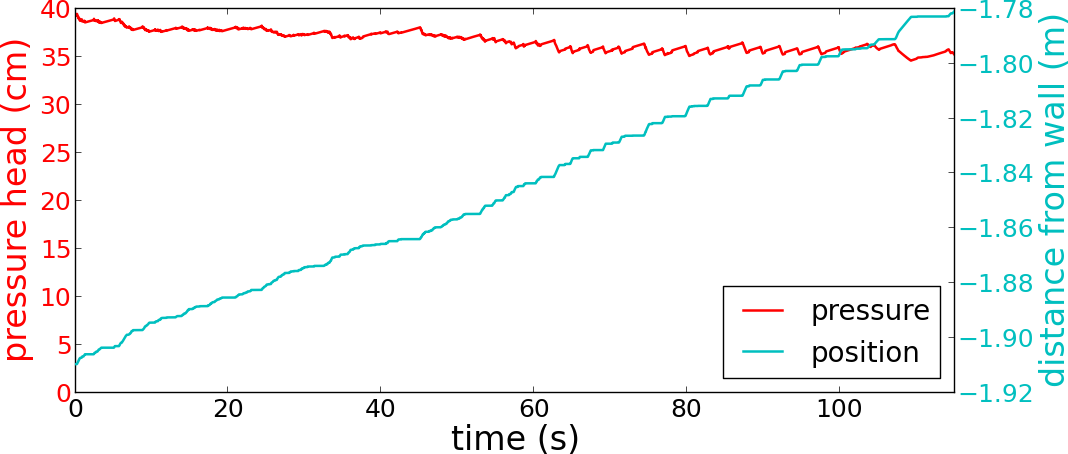

Next we consider model performance in simulating an experiment with densely packed sediment. In these experiments and simulations, initial failure of the sediment leads to a dilative response of the denser soil, which reduced the pore-fluid pressure during deformation, acting to retard motion. The pore-fluid pressure slowly rebounded after each precipitous drop, leading to semi-periodic stick–slip cycles (Figure 5).

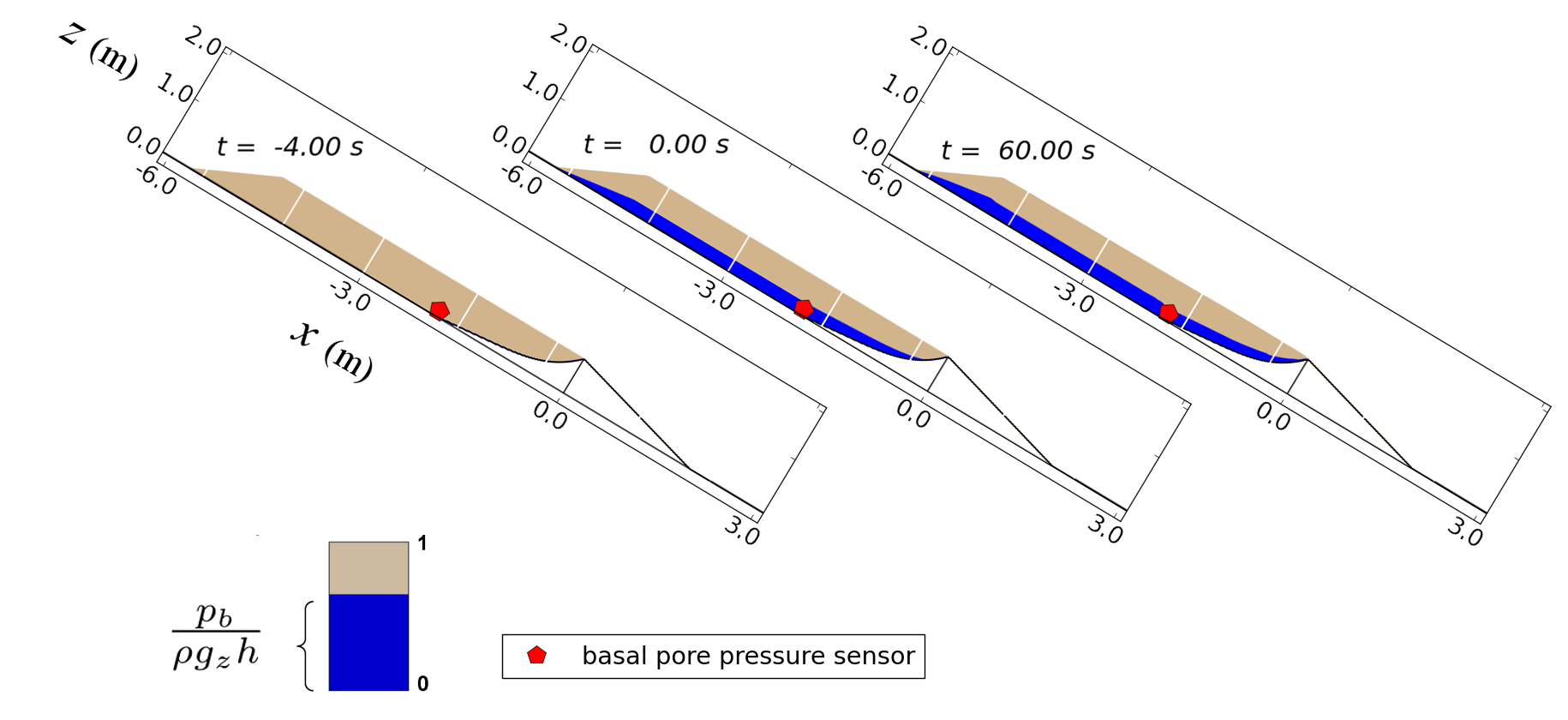

Gate-release experiments: downslope dynamics and runout.

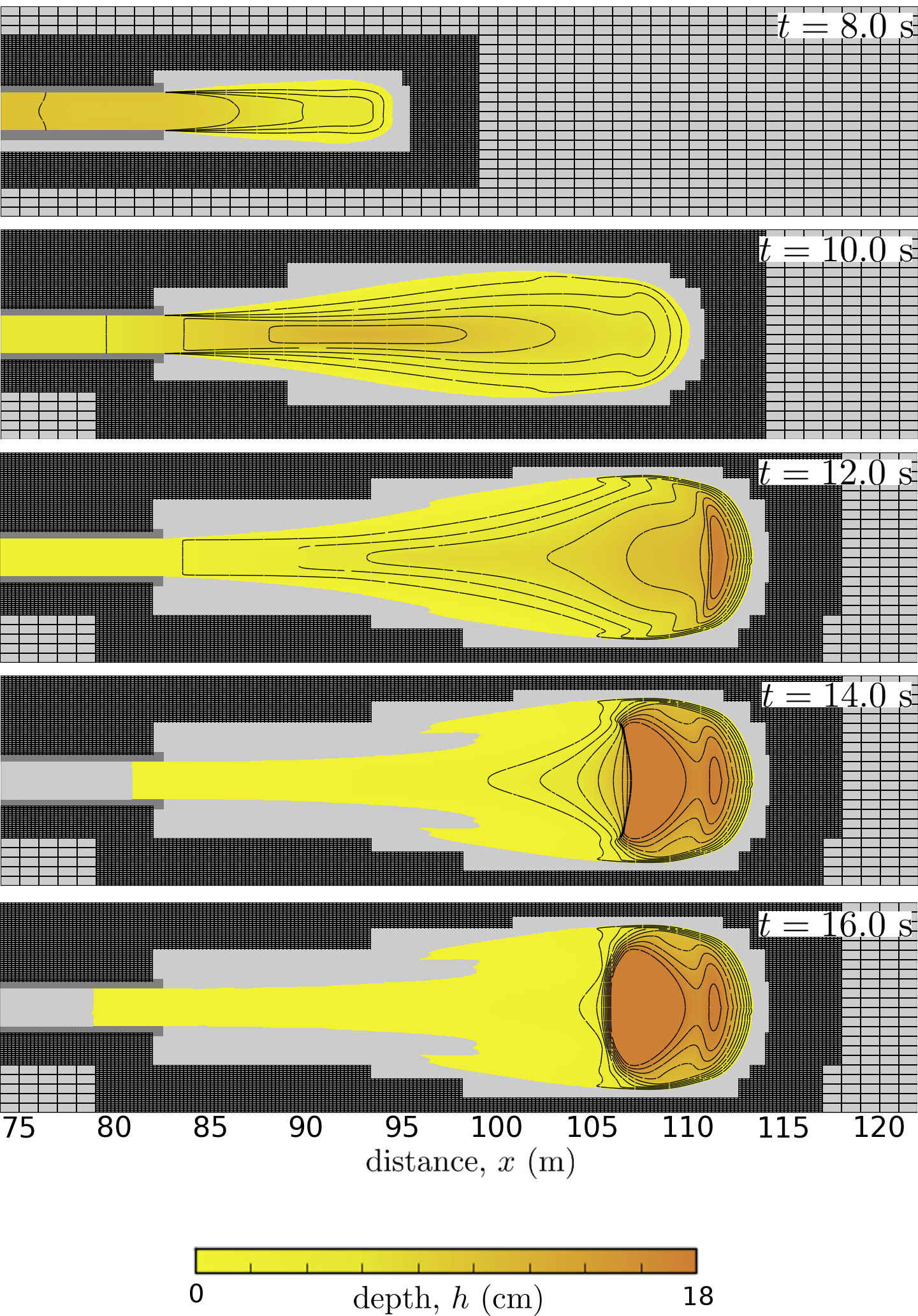

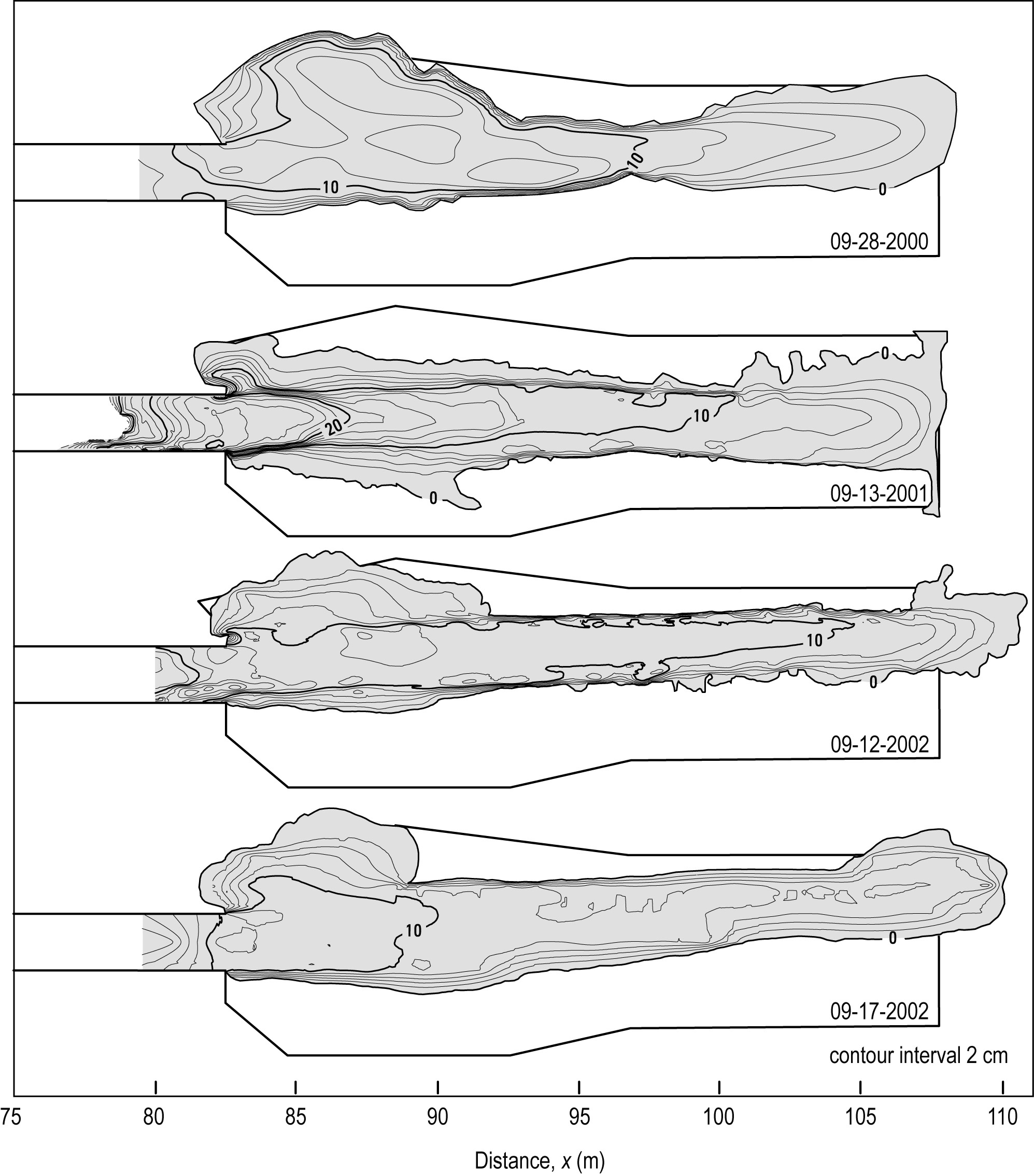

In this section, we investigate D-Claw’s ability to predict debris-flow dynamics, runout and deposition measured in a set of gate-release flume experiments. In these experiments, loose sediment was placed in a hopper behind a vertical gate near the top of the flume, saturated with water, and released by suddenly opening the gate (Figures 6-8). Upon releasing the headgate, the saturated mixtures quickly liquefied and developed into debris flows that descended the flume channel before emerging onto a nearly planar runout pad and forming deposits.

We focus on the mean behaviour measured in an aggregated set of eight experiments referred to as sand–gravel–mud (SGM) experiments due to the composition of the sediment, which contained about 6% mud-sized particles by dry weight (Iverson et al., 2010).

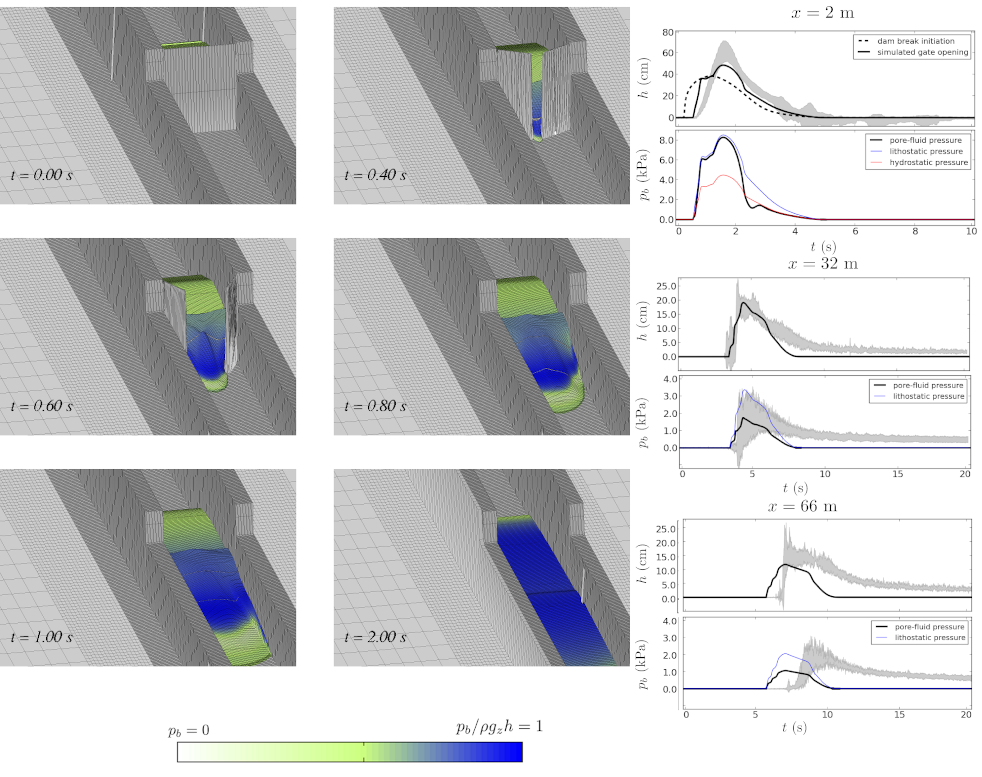

Figure 8 compares the measured flow depth at x = 2 m with model results obtained with and without the simulated motion of the headgate. Note that the gate slightly impedes the flow, resulting in a delayed and more abrupt rise in thickness as most of the flow reaches x =2 m. Figure 8 shows the computed basal pore-fluid pressure p, compared to the lithostatic and hydrostatic pressure for the computed thickness h, at 33 m and 66 m downslope. Measurements of the basal pore-fluid pressure in the experiments were not obtained at x =2 m. Figure 9 shows the depositional process on the runout pad.

Conclusions

We have derived a depth-averaged debris-flow model aimed at seamlessly simulating all stages of flow behaviour, from initiation to post-depositional debris consolidation. The model formalizes the hypothesis that the evolving debris dilation rate, coupled to evolution of pore-fluid pressure, plays a primary role in regulating debris-flow dynamics. The model’s representation of this role involves three key postulates. One postulate is that changes in the solid volume fraction m result from the interaction of the depth-averaged shear rate, dilatancy and effective stress. In turn, the evolving dilatancy angle ψ obeys tan ψ = m − meq, where the equilibrium solid volume fraction meq depends on the ambient stress state and shear rate. The second key postulate, interrelated with the first, is that a Darcy drag formula describes the effect of solid–fluid interactions on the relaxation of m towards meq. The third postulate is that flow resistance is dominated by basal Coulomb friction, which is affected by dilatancy and by pore-fluid pressure mediated by Darcy drag. The Darcy and Coulomb postulates are consistent with behaviour observed previously in replicable experiments. Therefore, relationships involving dilatancy represent the primary new hypothesis embodied by the model. The fact that dilatancy produces a leading-order effect in the normalized model equations enhances the prospects for conclusive model tests.

The depth-averaged debris-flow model described above constitutes a non-conservative hyperbolic system of partial differential equations with source terms. Additionally, the eigenstructure of the system has a familiar form, with two nonlinear characteristic fields similar to those of the shallow water equations and three contact discontinuities with propagation speeds equal to the flow velocity. The eigenstructure is simpler than that of many two-phase models and it avoids elliptic degeneracy.

The novel incorporation of depth-averaged dynamic granular dilatancy allows D-Claw to unify models for slope failure and flow initiation with those for debris-flow dynamics. Inclusion of dilatancy also results in novel evolution equations for the solid volume fraction and pore-fluid pressure, which are tightlycoupled through source terms. Because of the inherent sensitivity associated with the transition from a stable debris mass to a dynamic debris flow, it is necessary for the numerical schemes in D-Claw to reliably and stably resolve balanced steady states. For debris flows, the prevalent steady state arises from the counterbalance of longitudinal normal-force gradients, gravitational driving forces and basal shear resistance, the latter of which is strongly dependent on the evolving fluid pressure. Flow initiation occurs when this balance is slightly perturbed. In order to resolve this perturbation and the resulting dynamics accurately, D-Claw requires a specialized Riemann solver and a carefully designed splitting of the source term. Comparisons of D-Claw model output with results from two types of large-scale experiments indicate that the model can successfully simulate key features of debris-flow mobilization as well as debris-flow dynamics, runout and deposition. Model results show that in many cases the effects of persistent high pore pressure strongly suppress the effects of basal Coulomb friction, which is the primary source of flow resistance. This finding is consistent with experimental and field observations indicating that reduction of friction by high pore-fluid pressure is largely responsible for debris flows’ remarkable mobility.

References

- George, D.L. and Iverson, R.M., 2014. A depth-averaged debris-flow model that includes the effects of evolving dilatancy: 2. Numerical predictions and experimental tests. Proc. R. Soc. A, 470 (2170). pdf

- Iverson, R.M. and George, D.L., 2014. A depth-averaged debris-flow model that includes the effects of evolving dilatancy: 1. Physical basis. Proc. R. Soc. A, 470 (2170). pdf

- Iverson, R.M. and George, D.L., 2016. Landslides that liquefy: modeling mobility bifurcation and the 2014 Oso, Washington, USA disaster. Geotechnique, V. 66(3), 175–187. pdf

- Iverson, R.M., George, D.L., et al., 2014Landslide mobility and hazards: implications of the 2014 Oso disaster. R.M. Iverson, D.L. George, et al., 2015. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., V. 412, pp. 197–208. pdf

- Iverson RM, Logan M, LaHusen RG, Berti M. 2010, The perfect debris flow? aggregated results from 28 large-scale experiments. J. Geophys. Res. 115, 1–29. (doi:10.1029/2009JF001514)

- Iverson RM, Reid ME, Iverson NR, LaHusen RG, Logan M, Mann JE, Brien DL., 2000. Acute sensitivity of landslide rates to initial soil porosity. Science 290, 513–516. (doi:10.1126/science.290.5491.513)