Extending GeoClaw’s tsunami modeling algorithms to overland floods (2010). Case study: the 1959 Malpasset dam-break disaster.

This page features material and excerpts from:

Adaptive finite volume methods with well-balanced Riemann solvers for modeling floods in rugged terrain: application to the Malpasset dam-break flood (France, 1959). D.L. George, 2010. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids, 66(8): 1000–1018. pdf

Abstract

The simulation of advancing flood waves over rugged topography, by solving the shallow-water equations with well-balanced high-resolution finite volume methods and block-structured dynamic adaptive mesh refinement (AMR), is described and validated in this paper. The efficiency of block-structured AMR makes large-scale problems tractable, and allows the use of accurate and stable methods developed for solving general hyperbolic problems on quadrilateral grids. Features indicative of flooding in rugged terrain, such as advancing wet–dry fronts and non-stationary steady states due to balanced source terms from variable topography, present unique challenges and require modifications such as special Riemann solvers. A wellbalanced Riemann solver for inundation and general (non-stationary) flow over topography is tested in this context. The difficulties of modeling floods in rugged terrain, and the rationale for and efficacy of using AMR and well-balanced methods, are presented. The algorithms are validated by simulating the Malpasset dam-break flood (France, 1959), which has served as a benchmark problem previously. Historical field data, laboratory model data and other numerical simulation results (computed on static fitted meshes) are shown for comparison. The methods are implemented in GEOCLAW, a subset of the open-source CLAWPACK software. All the software is freely available at www.clawpack.org.

Background

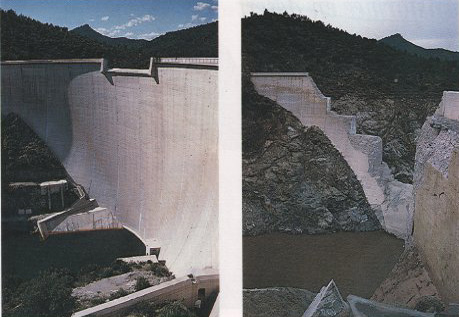

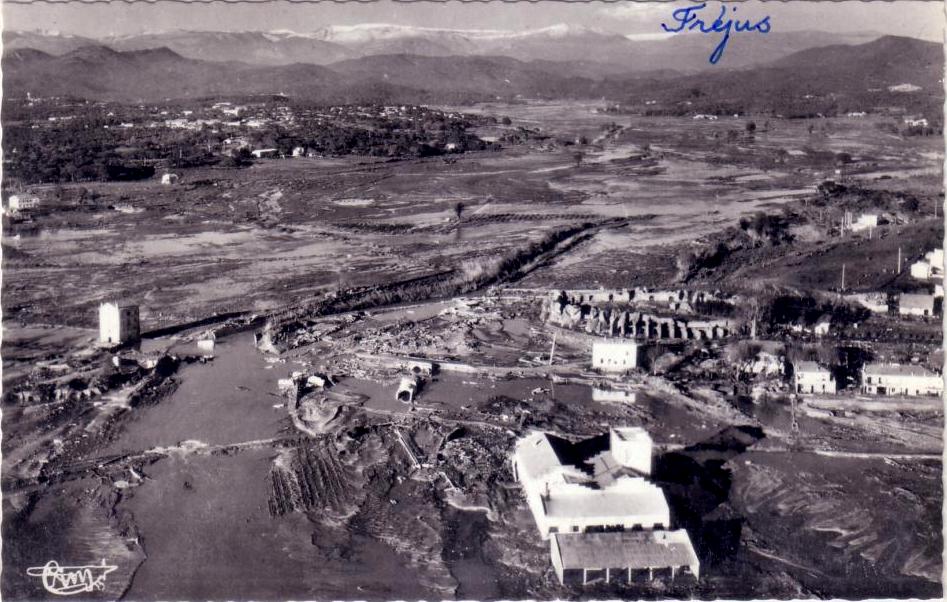

The Malpasset Dam was located in a narrow gorge above the steeply banked Reyran River Valley about 12 km north of the town of Frejus on the French Riviera. The double arch dam was 66.5-m high and approximately 223-m wide along the top arch. For the 5 years following the completion of the dam in 1954, the reservoir behind the dam was slowly filled, nearing capacity in November 1959. During a period of intense rainfall from November 19 to December 2, the reservoir reached the crest of the dam, prompting the opening of the outlet gates at 6 P.M. on December 2. The dam failed catastrophically at 9:14 P.M., sending a massive wave 40–60-m high into the winding gorge below. Although there were no surviving eyewitnesses, the dam failure was believed to have been sudden and explosive. The resulting violent flood wave altered the landscape and destroyed bridges, roads and several buildings along its path down the river gorge before flooding the low-lying Reyran River Valley surrounding the town of Frejus. The flood waters finally reached the Fr´ejus Gulf 21 min later. There were 412 casualties.

Testing outburst flood with GeoClaw

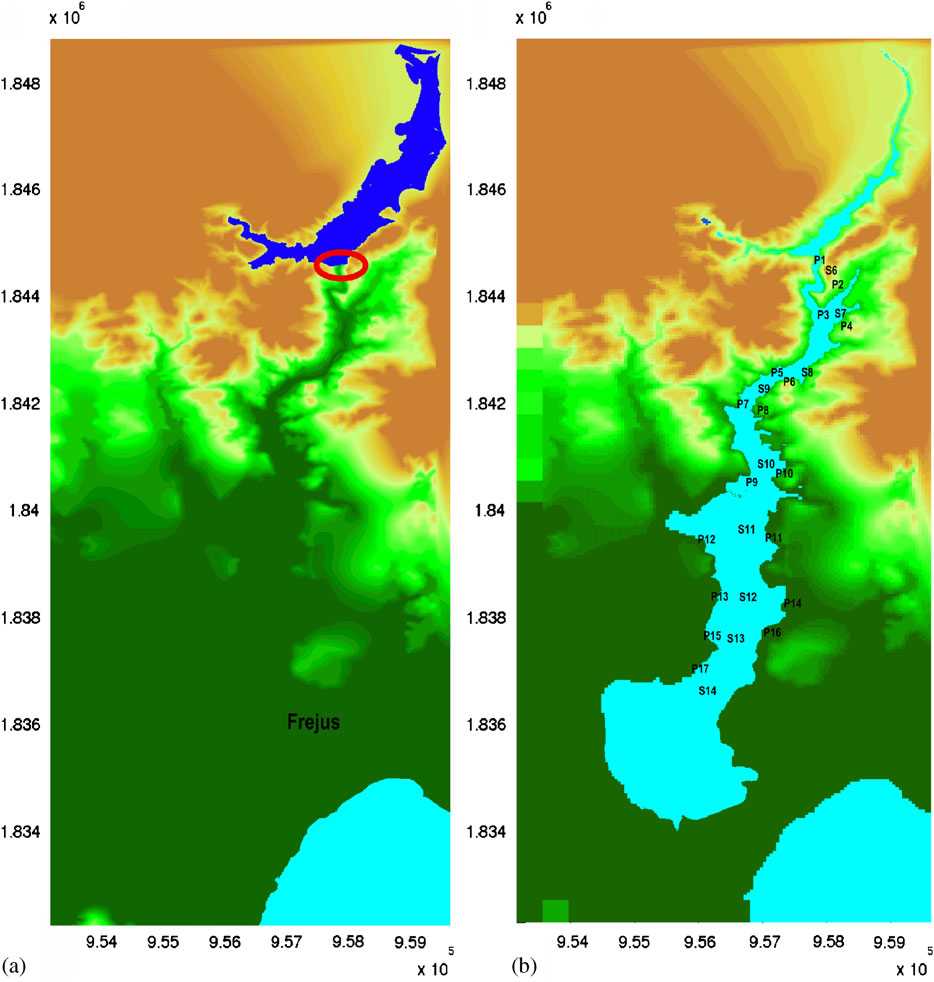

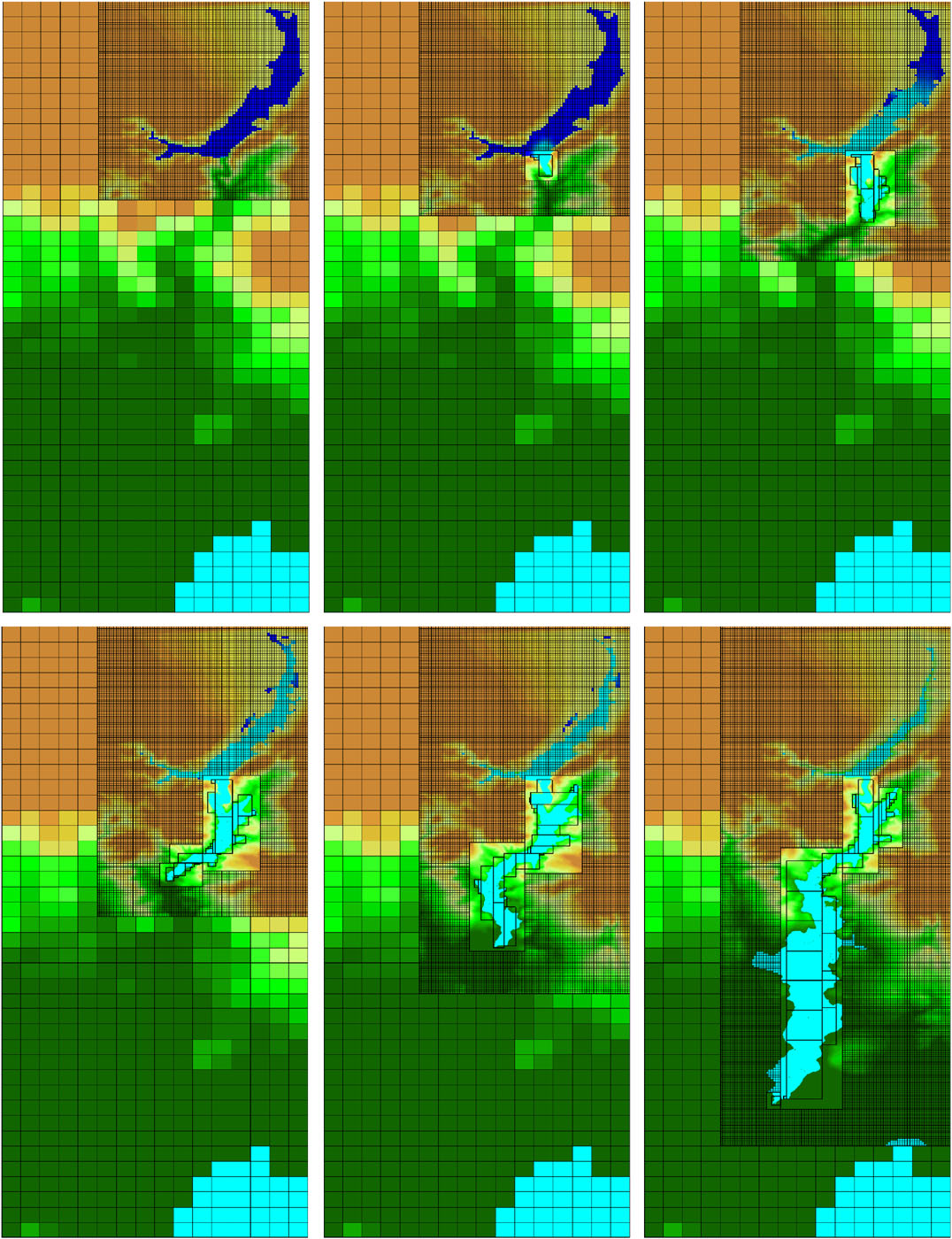

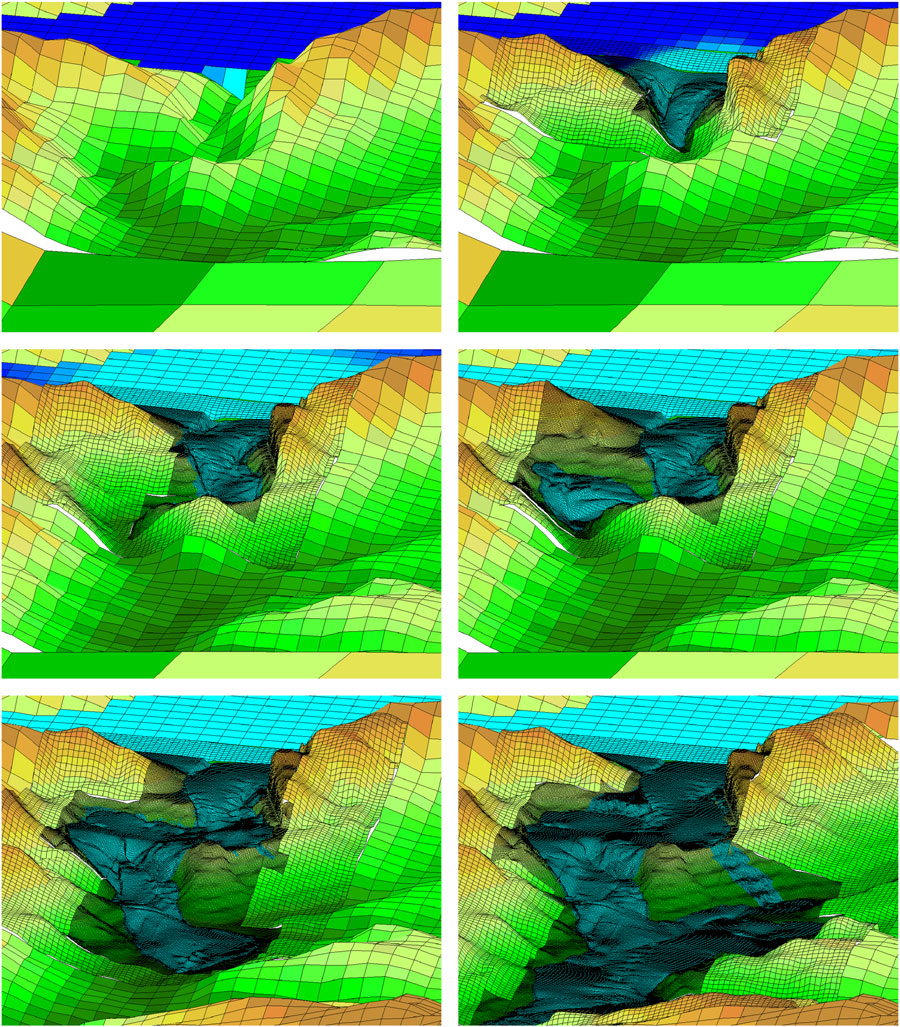

GeoClaw’s algorithms are more generally applicable to free-surface water flows over topography, such as with overland flooding in steep terrain. In 2010 this was applied to the Malpasset dam break disaster in southern France, 1959 to test the ability to extend GeoClaw’s tsunami modeling methodology to general overland floods (George, 2010). For instance, this problem was used to test the accuracy of AMR for the resolution of flood waters descending through a complex drainage within a larger bounding domain, avoiding the need of topographic mesh generation or prohibitively large uniform grids. This modeling also involved an enhancement of the treatment of wet-dry interfaces within GeoClaw’s Riemann solver (George, 2008), (particularly where topographic jumps are high in steep terrain) through appropriate modifications to ghost cell problems (George, 2010).

Comparison with field and model data

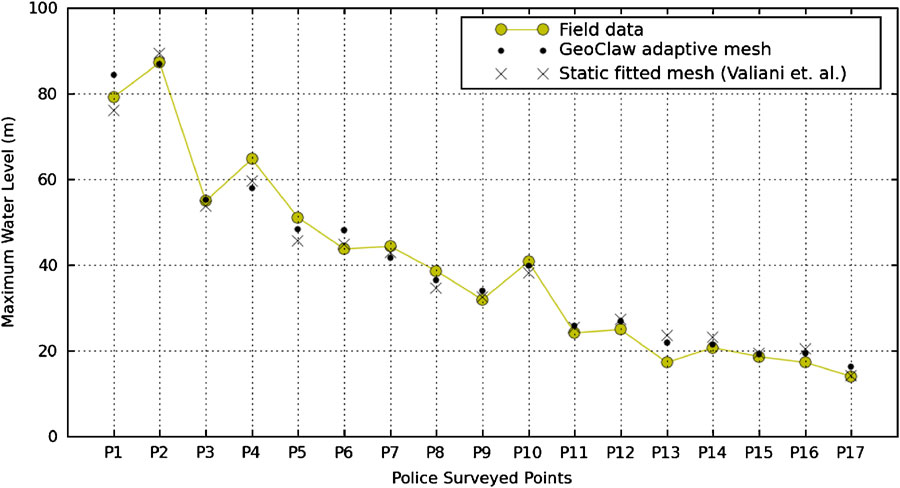

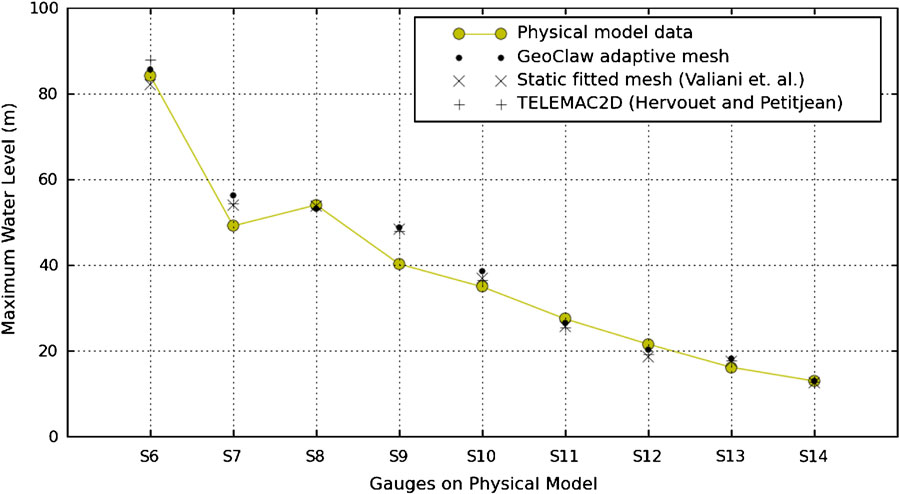

The results of the GeoClaw simulations were compared against historical survey data, physical model data and results from other numerical codes. All of the simulation data compare well with the empirical data, supporting the conclusion reached at the CADAM workshops (Alcrudo, 1999) that the shallow-water equations are a reasonable model for flood simulation and risk assessment even in steep terrain. The only tunable physical parameter in the simulations was the Manning coefficient, which was chosen to be 0.033 as suggested by CADAM participants.

References

- Alcrudo F (ed.). Proceedings of the 4th CADAM Meeting. CADAM: Zaragoza, Spain, 1999.

- Berger, M.J. and Colella, P., 1989. Local adaptive mesh refinement for shock hydrodynamics. J. Comput. Phys., 82: 64-84.

- Berger, M.J., George, D.L., LeVeque, R.J. and Mandli, K.T., 2011. The GeoClaw software for depth-averaged flows with adaptive refinement. Advances in Water Resources, 34: 1195–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.advwatres.2011.02.016 pdf

- George, D.L., 2008. Augmented Riemann solvers for the shallow water equations over variable topography with steady states and inundation. J. Comput. Phys., 227(6): 3089–3113. pdf

- George, D.L. 2010. Adaptive finite volume methods with well-balanced Riemann solvers for modeling floods in rugged terrain: application to the Malpasset dam-break flood (France, 1959). Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids, 66(8): 1000–1018. pdf

- LeVeque, R.J., 2002. Finite volume methods for hyperbolic problems. Texts in Applied Mathematics, Cambridge University Press.

- Valiani A., Caleffi V., and Zanni A., 2002. Case study: Malpasset dam-break simulation using a two-dimensional finite volume method. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 128(5):460–472.